It started with a sore shoulder

In June 2021, I developed shoulder pain. Nothing dramatic. My GP thought it was bursitis, maybe some impingement. I did what you do: physio, rehab, patience. For six months, I tried to fix a sore shoulder.

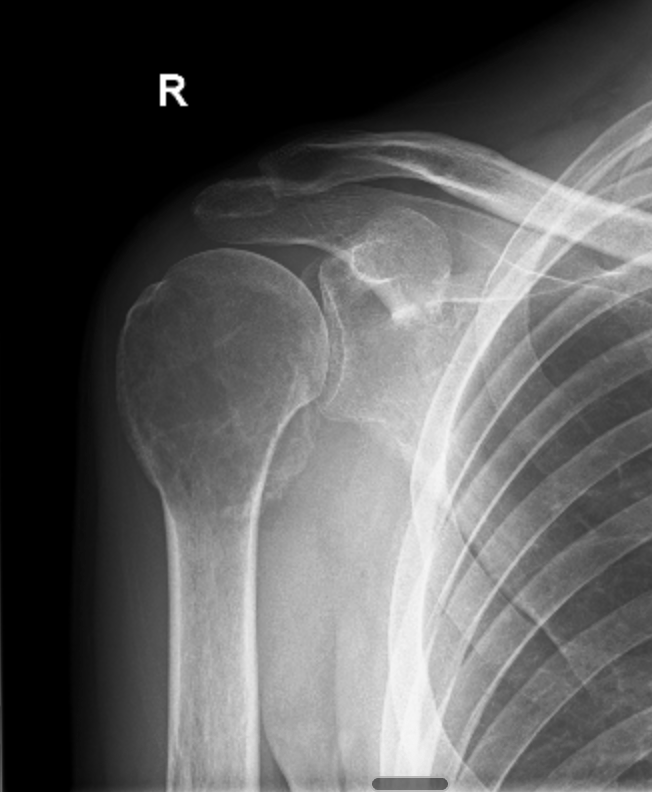

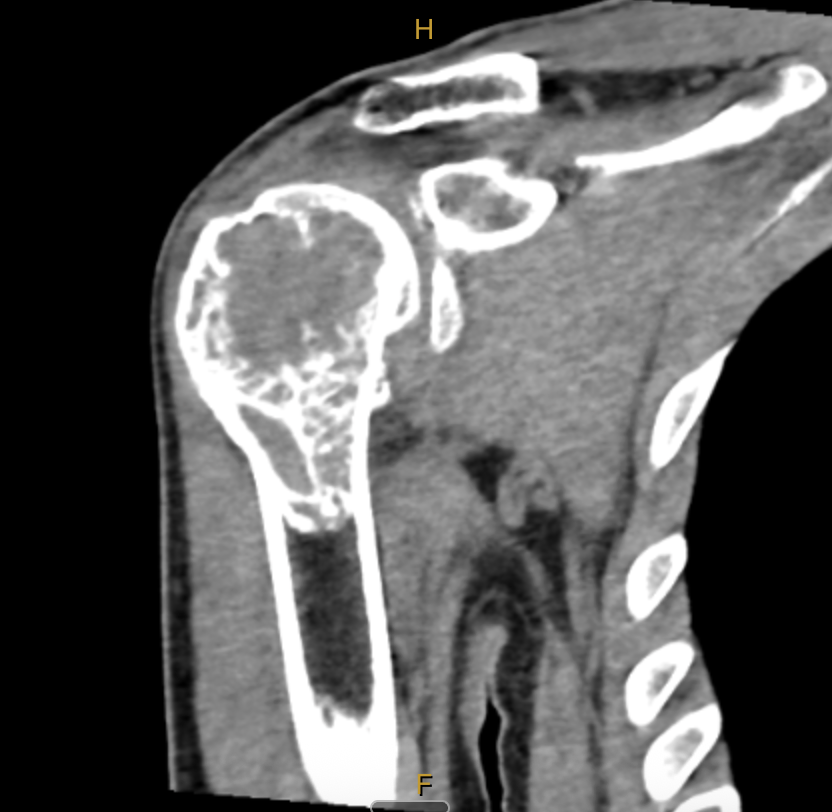

Then, in early December, I was woken in the middle of the night by excruciating pain. We were living regionally at the time, so it took a few weeks to get an MRI. That scan happened on the 21st of December 2021. Two days later, two days before Christmas, I sat in a room and was told I had a giant cell tumour of bone in my right proximal humerus.

Giant cell tumour of bone, or GCTB, is a rare bone tumour that affects roughly one to two people per million. It's locally aggressive, has a high recurrence rate, and the treatment options are limited: surgery, or a drug called denosumab. That's essentially it.

I was 31 years old, and I'd just been told my shoulder was being eaten from the inside.

Denosumab

Within days of that diagnosis, my wife Katie and I packed up and moved to Melbourne. In January 2022, I met my first surgeon. The clinical picture was confronting: the tumour was large, it had destroyed significant bone stock, and the surgical margins were going to be tight.

The plan was to start denosumab, a monoclonal antibody that targets RANKL, the key driver of the giant cells that give the tumour its name. The idea was that denosumab could help regrow bone stock, improve the surgical margins, and give us a better shot at limb salvage rather than going straight to a total reverse shoulder replacement.

I did six doses, the standard loading protocol. The bone stock improved. But the margins were still insufficient for limb salvage surgery. And the recommendation from my surgeon was clear: we should go to reverse shoulder replacement.

Pushing back

I'd gone through months of denosumab treatment, and the outcome was still a shoulder replacement. That didn't sit well with me.

There's a moment in this journey where the question changes. It stops being "What do I do?" and starts being "Why aren't there better options?"

I started reading. I started asking questions. I started looking at what was being studied, what was being tried, what was being ignored. And what I found was a gap. GCTB is rare enough that the research community is small. The standard of care hasn't fundamentally changed. And there were very few people pushing for that to change.

I was young. I understood the risks: a high recurrence rate, tight margins, the possibility of needing to come back and do it all again. But I also understood what a reverse shoulder replacement meant for the rest of my life. And I'd read enough to know that limb salvage was worth fighting for.

I sought a second opinion. I found a surgeon at St Vincent's Hospital in Melbourne who was willing to partner with me on a limb salvage approach, even knowing the margins were thin.

In May 2022, I had limb salvage surgery: intralesional curettage with bone cement and a plate. That decision, to advocate for myself, to challenge the recommendation, to find a clinician who would work with me rather than just for me, that was the moment I became a researcher and an advocate. I just didn't know it yet.

Recurrence

For a while, it looked like we'd got away with it. But in February 2023, the signs came back. Pain in the shoulder, limited movement, that familiar feeling that something wasn't right. Imaging confirmed what we feared: the tumour had recurred.

Locally aggressive, high recurrence rate. The textbook had warned us. And now I was facing another decision.

More limb salvage surgery, with even thinner margins. Reverse shoulder replacement. Or go back on denosumab, manage the tumour medically, buy time, and hope that the treatment landscape would evolve.

I chose denosumab. Every four weeks, an injection. The thinking was: long-term, there might be better options coming. And even if there weren't, we could push out the timeline before a replacement became necessary.

The long game

And that's what we've been doing. After about a year at four-week intervals, we started trying to taper, gradually extending the time between doses.

The first attempt to push beyond five weeks failed. At five and a half weeks, the pain came back. We reset. Tried again a few months later. This time it held. Eight weeks. Then nine. Then twelve. Sixteen. And most recently, twenty weeks between injections.

Denosumab tapering journey

Weeks between doses, March 2023 to December 2025

It's a process of learning to read your own body, distinguishing between normal aches and the signals that something deeper is happening. Every extension is an experiment. Every pain-free week is a small victory.

From patient to advocate

That advocacy instinct that kicked in before my first surgery never stopped. Navigating the medical system with a rare condition taught me things you can't learn from a textbook: how to seek second opinions without burning bridges, how to coordinate across multiple specialists, how to make sense of conflicting information, and how to make decisions when there are no clear answers.

Today, I work as an independent researcher and consumer advocate focused on GCTB. I'm a consumer advisor on precision care medicine research at UNSW. I partner with Rare Voices Australia and Rare Diseases NSW. I monitor every publication on GCTB treatment and outcomes that I can find. And I'm working toward something specific: a pilot research program to test novel treatment approaches.

Because surgery and denosumab shouldn't be the end of the conversation. They should be the beginning.

Why I do this

Going through this made me acutely aware of how alone patients can feel when navigating a complex medical situation, especially with a rare condition where your GP, your surgeon, and even your oncologist may have limited experience with your specific disease.

I built a skillset out of necessity: researching my own condition, coordinating my own care across specialists, making informed decisions about treatment options when the evidence base is thin. And I realised those skills are transferable. The challenges I faced aren't unique to GCTB. They're common to anyone dealing with a complex, multi-specialist medical journey.

That's why I now offer patient navigation services. Not medical advice. I'm not a doctor. But practical, experienced support to help people feel less alone and more empowered as they navigate their own path.

Advocacy isn't a luxury. In rare disease, it's a survival strategy.